Rishma Dunlop

Somewhere, a woman is writing a poem

in the twilight hours of history, lavender turning to ash,

as time spills over and the moon unfurls her white-pitched fever in

the songs of jasmine winds. The young woman I was climbs the

stairs, the moon's pale alphabet filling her. She tucks her child into

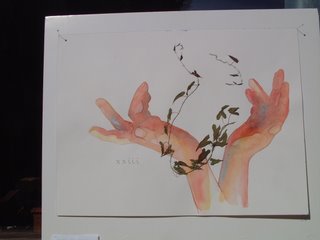

bed, bends over her desk in the yellow lamplight, frees her hand

to write, breaking through the page like that Dorothea Tanning

painting where the artist's hand gashes through the canvas, fingers and

wrist plunged to the bone. She writes a dark, erotic psalm, an elegy,

a poem to grow old in, a poem to die in.

Somewhere, a woman is writing a poem,

as she gives away the clothes of her dead loved ones,

stretching crumpled wings, her words rise liquid in the air,

rosaries of prayer for the dying children, for the ones who

have disappeared, the desaparecido, and for the ones who

have been murdered. She writes through the taste of fear and

rage and fury. She writes in milk and blood, her ink fierce and

iridescent, rooted in love. Somewhere, a woman who thought

she could say nothing is writing a poem and she will sing forever,

blooming in the dark madness of the world.

Memento Mori

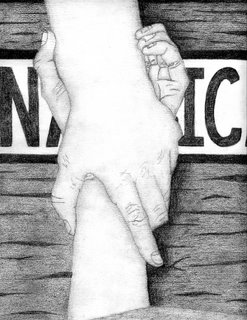

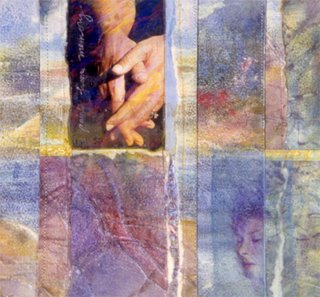

Estelle unbuttons her blouse, lays my

hand on the jagged scar where her breast

used to be. She wants me to tell her she is

still beautiful.

I feel her heart beneath the ribbed wall

milk-veined softness knifed into a cavern.

She tells me her husband has not been able

to look at it yet, this place on a woman's body,

nuzzled and suckled and cupped by infants

and lovers.

Her gesture recalls my

first lover, his teenage body, long six foot

stretch, lean limbs, every rib visible, the

surgical scar after the mending of a collapsed

lung. I used to breathe into that curved mark

above his heart, lay my head against its pulse.

Three decades later, I realize my lover

has that same six foot stretch of bones, that

tender ribcage.

How we return, full cycle, to first love.

While ashes that rise meet ashes that fall

we become the world for a while, the rose

of each lung blooming inside.

All this contained in the memory of my hand

on Estelle's heart, her absent breast, sweet flesh

excised into terrible beauty. I tell her she is beautiful,

despite her husband's averted gaze, that she will continue

to be loved.

It can not be otherwise.

For her mother has named her with human faith.

Estelle, her name a star.

Poems from Reading Like a Girl, Windsor: Black Moss Press, 2004. Copyright ©

Rishma Dunlop 2004